LINGJIE WANG

...VERBINDUNG, CONNECTION

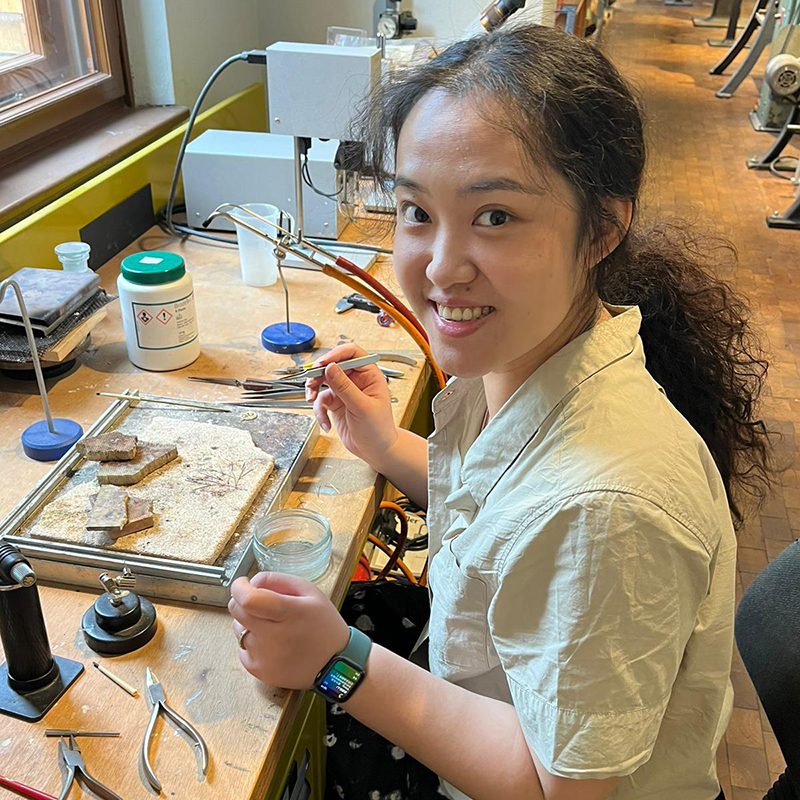

Stipendiatin 2024

Lingjie Wang is a contemporary jewelry artist. She studied Schmuck at Hochschule Pforzheim and received her MA from the Royal College of Art in London. Her work has been exhibited and recognized internationally, including the 3rd Prize of the BKV Prize for Young Applied Arts, participation in Schmuck 2025, Ornamenta’s Uncommonly Brilliant Conversation in Pforzheim, and KORU8 in Finland.

Drawing upon the Fungi project—where mycelium forms an intricate, living network for the exchange of information and matter—I approach historical techniques as a kind of cultural mycelium: a connective tissue that transcends temporal and spatial boundaries to intertwine with contemporary contexts and methodologies. This body of work is grounded in the exploration of connection and repair, not merely as themes but as processes. Through making, I came to understand repair as a distinct mode of connection—one that does not simply restore, but reconfigures and reanimates relationships.

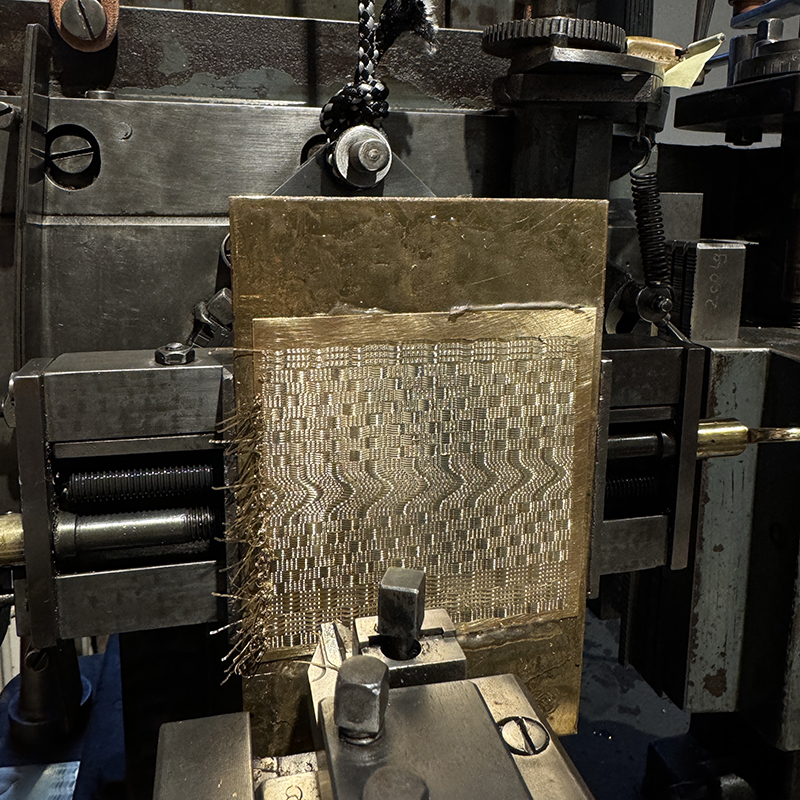

Among the various techniques I engaged with, the raw, elemental force of stamping stood out. Its immediacy and intensity collapse distinctions, generating a synthesis that feels both violent and generative. The act becomes a metaphor for how disparate elements—histories, identities, materials—can be forcefully unified into something new. In contrast to the overwhelming inertia of systems and the passage of time, individual gestures may appear insignificant. Yet it is precisely within these gestures that deeply personal and authentic forms of connection emerge—ephemeral, intimate, and essential.

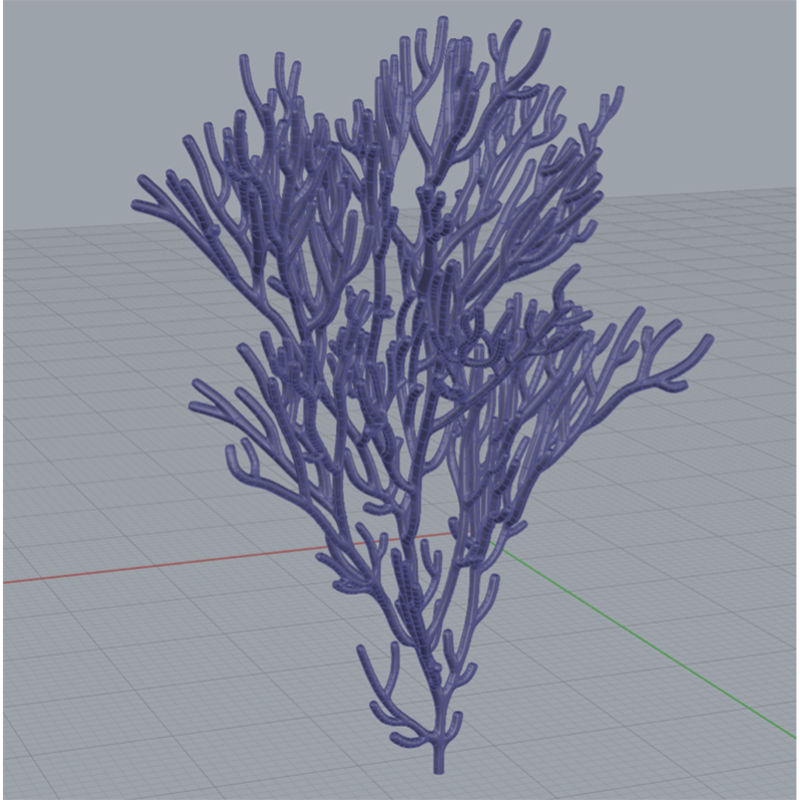

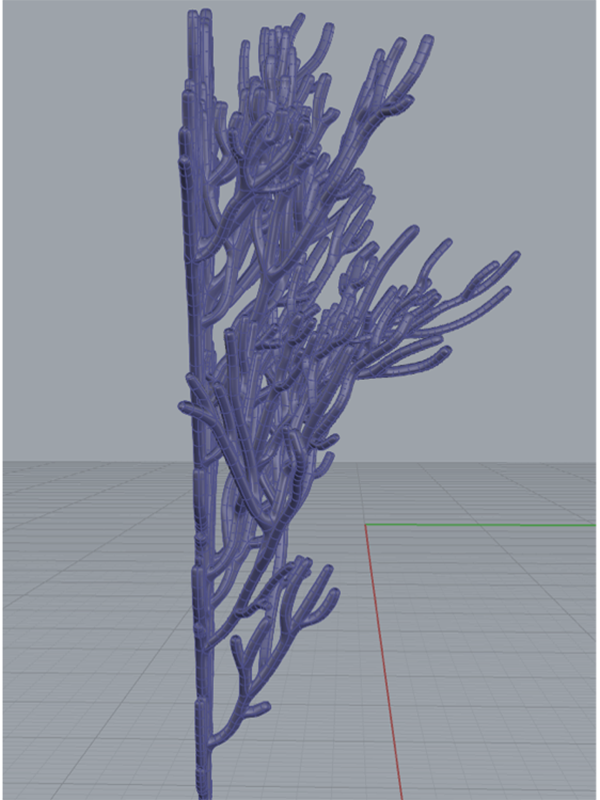

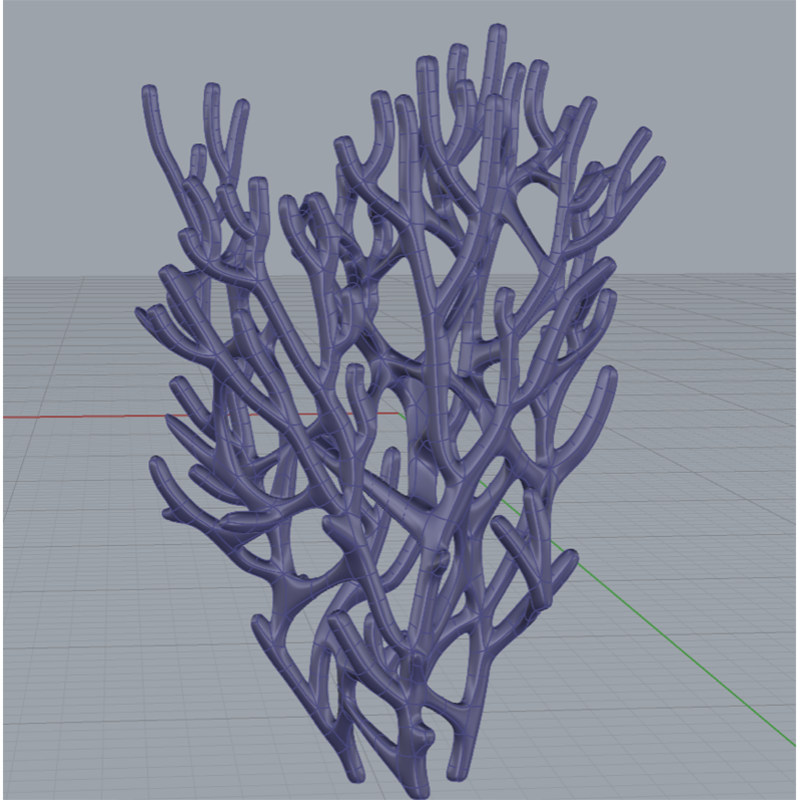

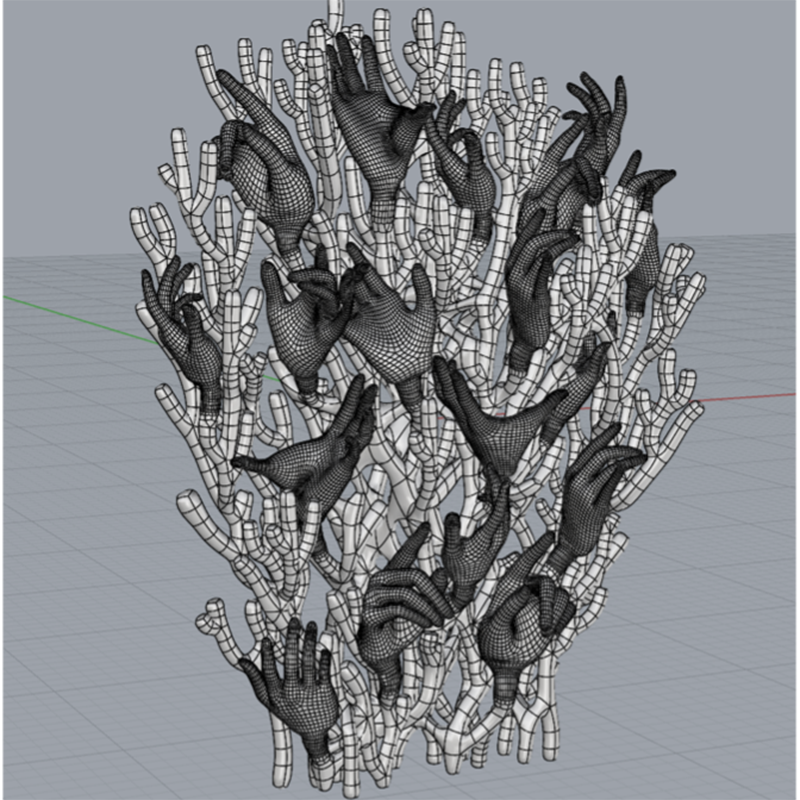

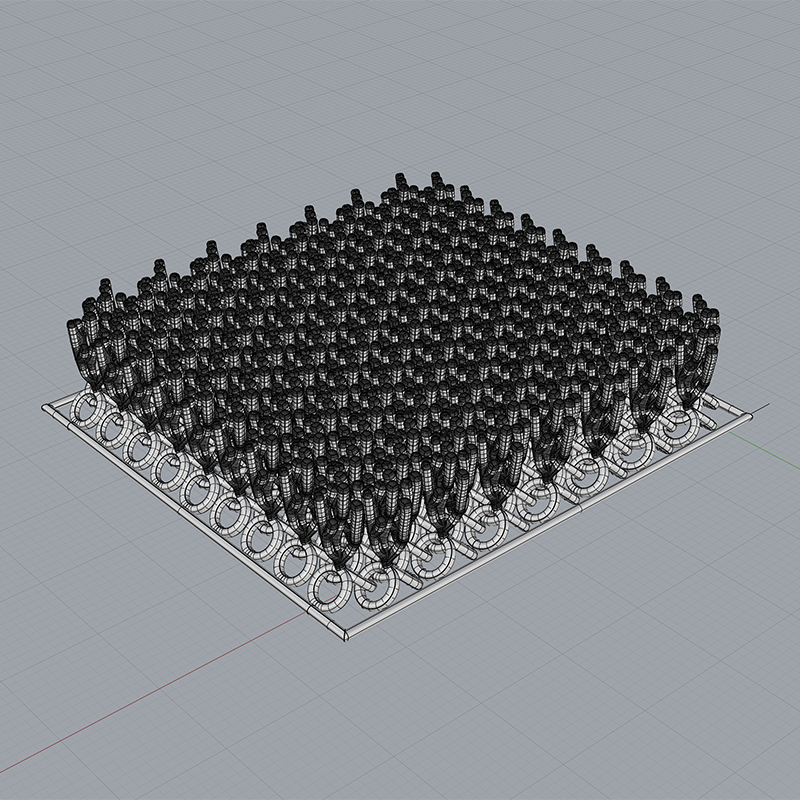

At the outset, my vision for the final works was intentionally undefined. I allowed intuition to guide the process, beginning with the construction of mycelium-like forms in Rhino using two distinct structural approaches.

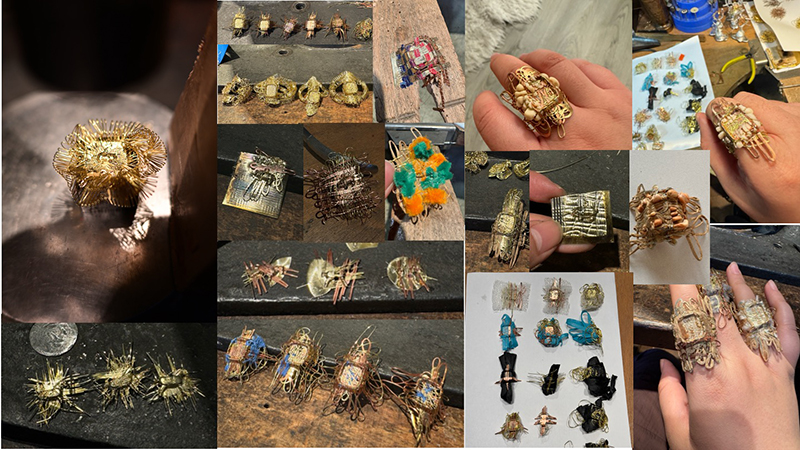

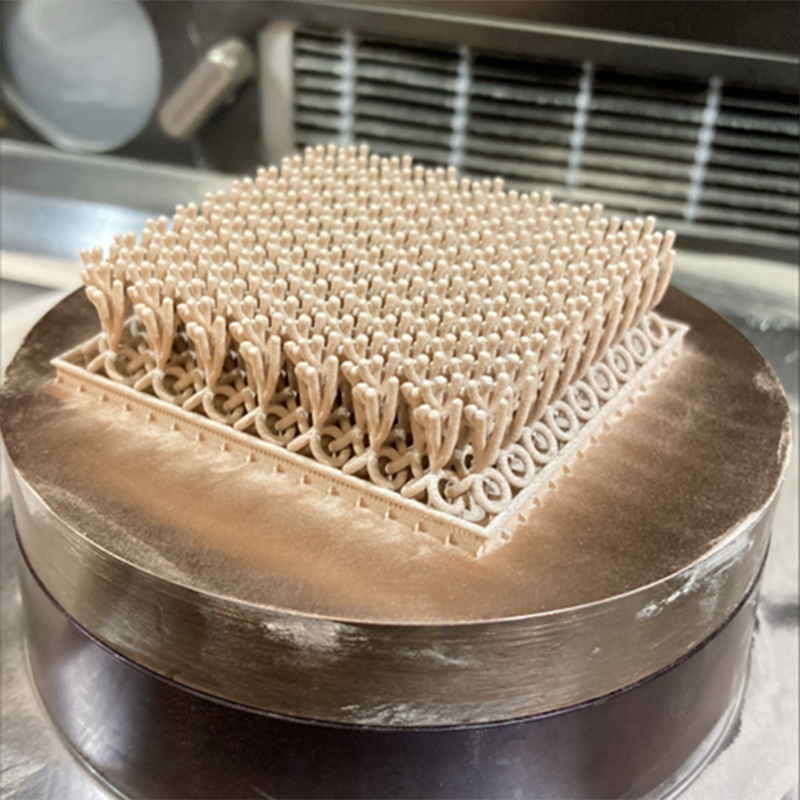

My initial concept involved stamping some animals of 3D printed branches. These forms, made of extremely thin material, required an understanding of the technical limitations of 3D printing—particularly the optimal thickness and structural integrity necessary for successful stamping.

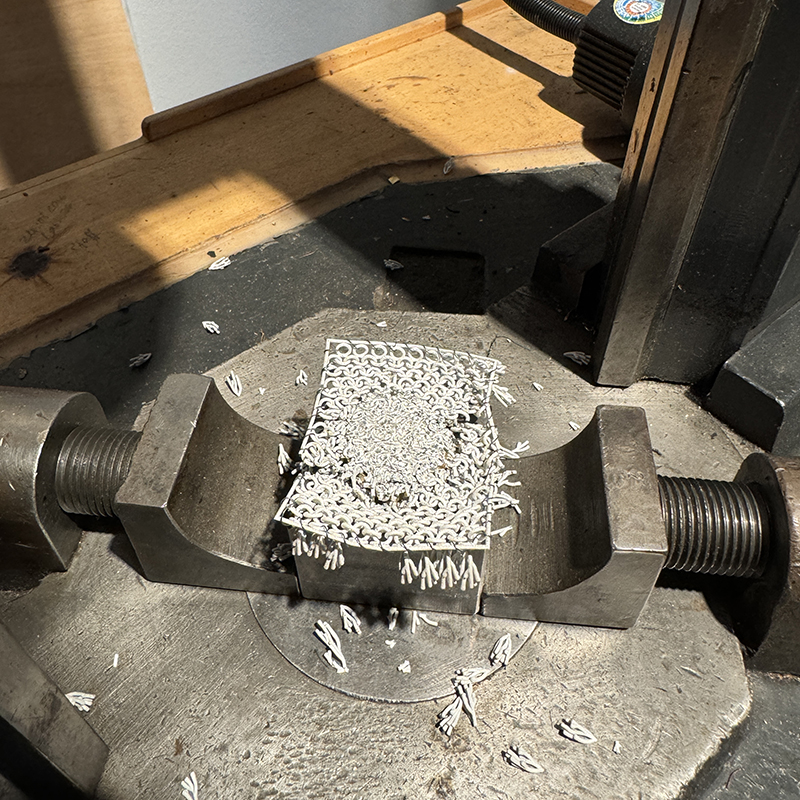

To explore these parameters, I fabricated a series of sample structures, soldering them by hand in preparation for initial stamping tests. In my first trial, I sawed the upper die from its base, intending only to impress the silhouettes of animals onto the metal mycelium. However, due to the strength and sharpness of the sawed edge of the die. The first stamping was unsuccessful and the die itself was damaged. From this experiment, I discovered that a material thickness of 0.6 mm produced the most compelling visual results—delicate yet legible—and thus selected it as the standard for subsequent trials.

My first attempt

Over a week, I soldered various metal structures of differing thicknesses, experimenting with their response to force. Unexpectedly, I discovered that impact alone could function as a kind of adhesive—temporarily fusing components without solder. I was also captivated by the visual contrast between frosted and polished surfaces, a result of the die transferring its sheen onto the stamped subject. This interplay between texture and reflection became a central aesthetic consideration, emphasizing the transformative power of pressure and material memory.

0.8mm, 2 layers, soldered, brass

0.6mm, 3 layers, soldered, brass

0.5mm, without solder, brass

I deeply enjoyed the exploring process of making experiments in the jewellery department in the museum. I introduced diverse materials into the stamping process—including paper, fabric, polymer clay, and others. In addition to mycelium-inspired structures, I constructed new forms from these materials to examine how they responded under pressure. I also integrated stamping with other techniques, such as Guilloché and sandcasting.

From this broad range of experiments, three directions emerged as particularly compelling, and I developed them into final works:

-

1. Guilloché × Stamping

2. Paper-wrapped Silver Wire × Weaving × Embossing

3. Stamping × Sewing

1. Infinite growing ring

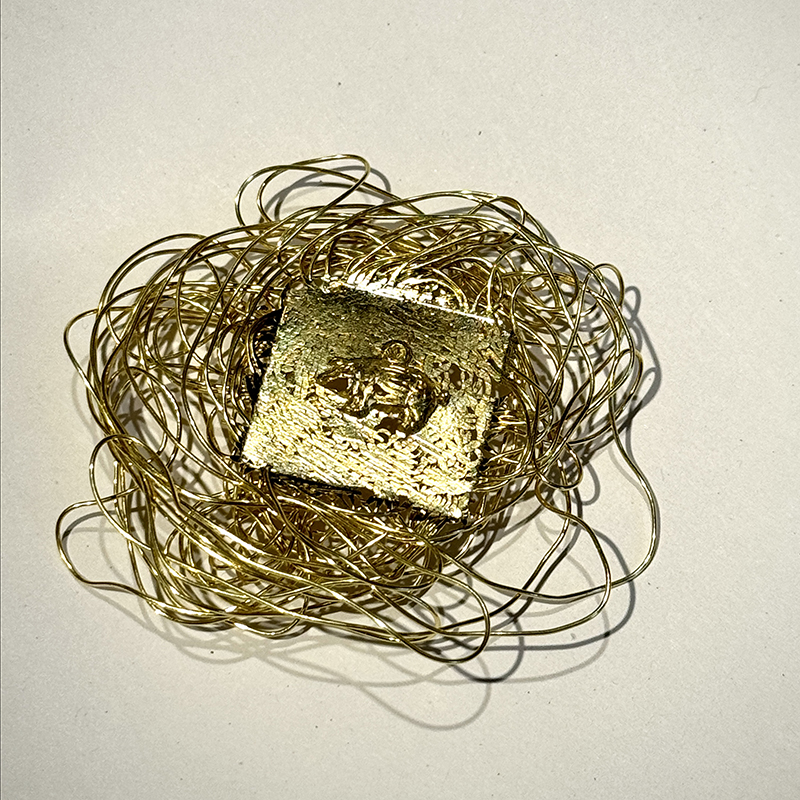

The first series, Infinite Growth Ring, draws inspiration from the expanding nature of hyphae within the earth. Their continual motion evokes the intangible moment when a connection begins to establish.

Silver wires are woven and stamped to create the ring’s head part. I then buried them in sand and cast molten silver, allowing it to flow freely—seeking out connections. This moment of dynamic interaction is suspended in time, captured in solid metal. I intentionally refrained from shaping the components to perfectly fit the die. When worn, the ring resists static form: the metal wires overflow the mold’s edge, creating an animated, living impression. Like mycelium extending their network, the ring redefines the boundary between object and body, between finger and form. Hence, the name Infinite Growth Ring.

My initial intention was to combine metals of the same type but with different surface treatments, incorporating them through both weaving and stamping. However, during casting, the heat-sensitive properties of the materials altered their coloration. But I was still interested in seeing how different metal with different colours can be integrated in one piece, so I wove cooper with silver and treated them with heat after casting.

after being stamped

after being cast

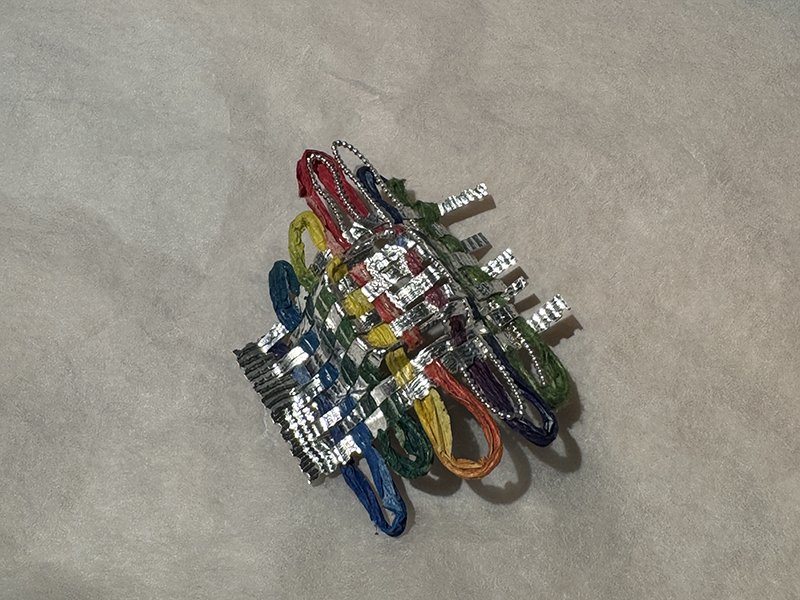

As an extension of the Infinite Growth concept, I also explored the use of paper-wrapped metal wire. In this approach, silver wires are slowly hand-woven to form ring bands, emphasizing a slower tempo of making compared to casting. After weaving, the surface is stamped, revealing the underlying silver and creating a tactile and visual contrast between embossed and untouched areas.

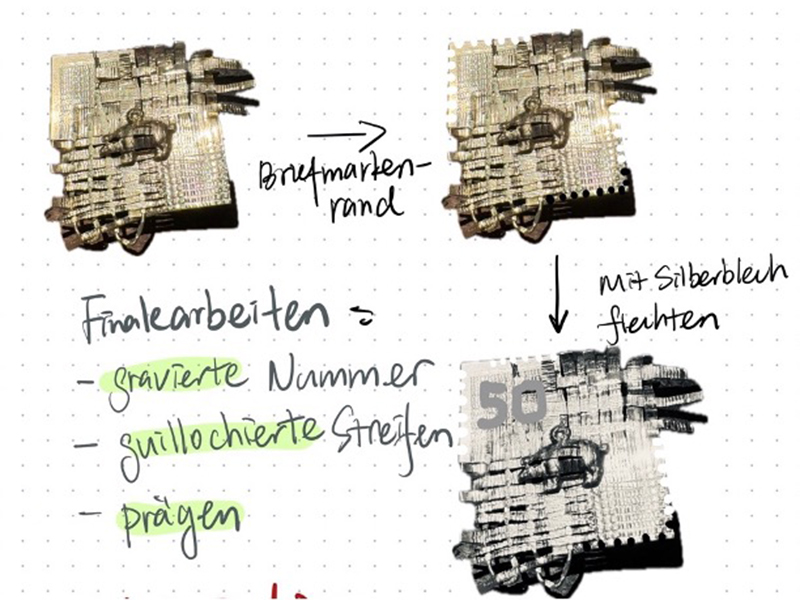

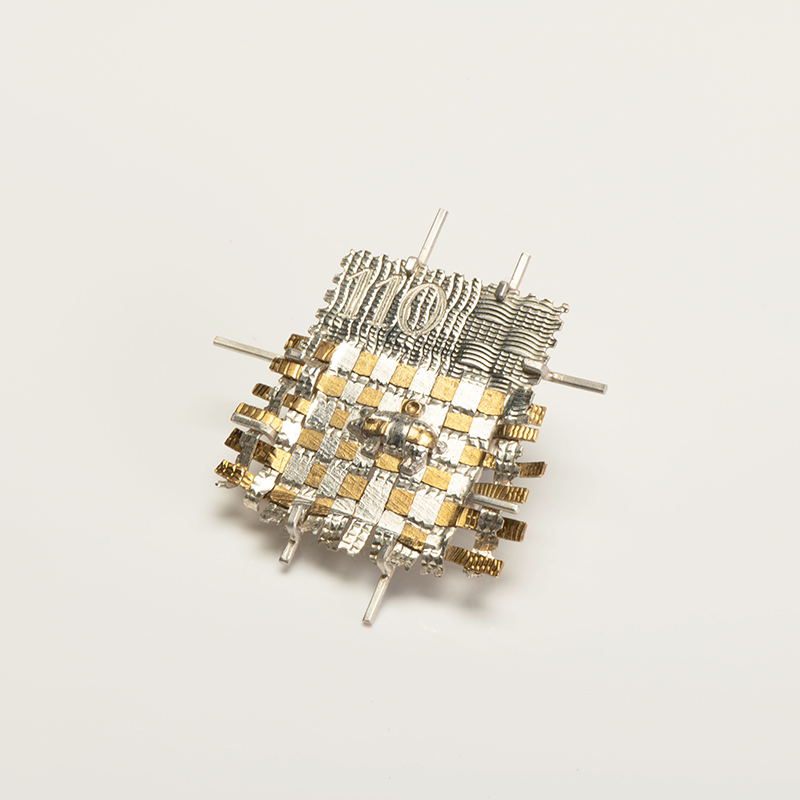

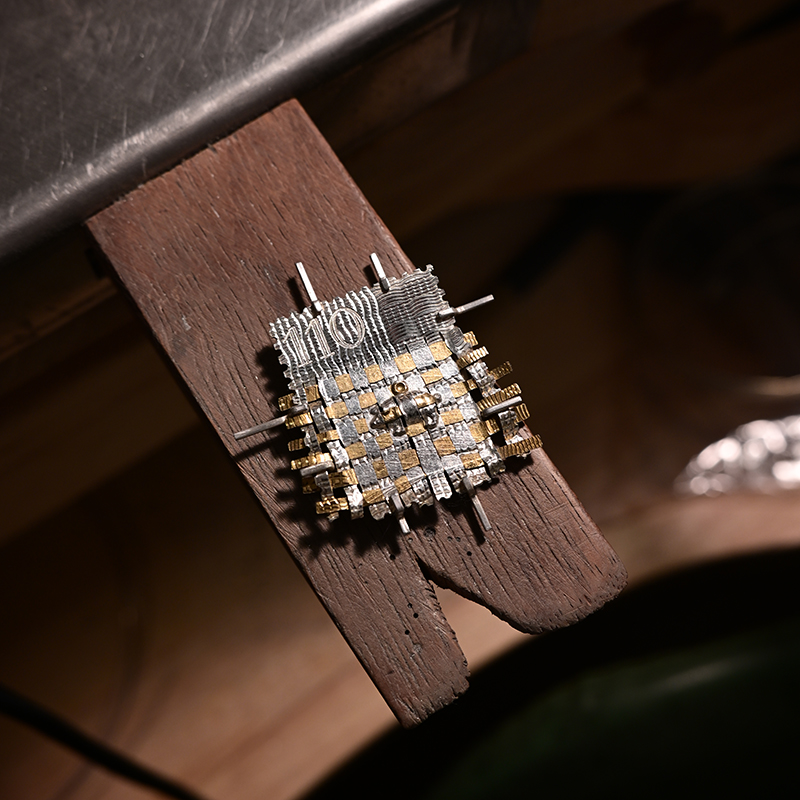

2. Patchwork stamp brooch

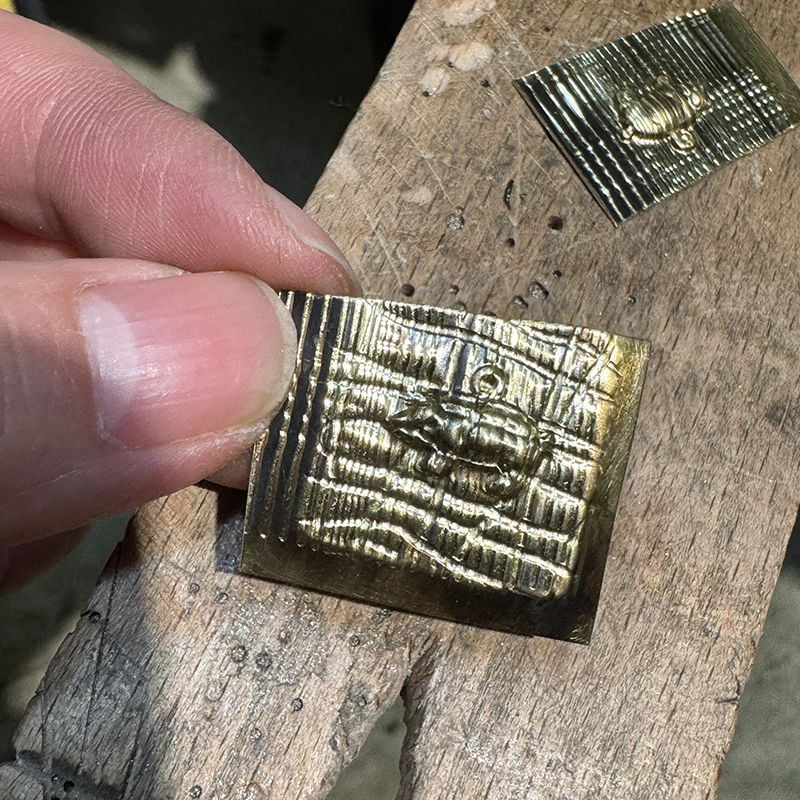

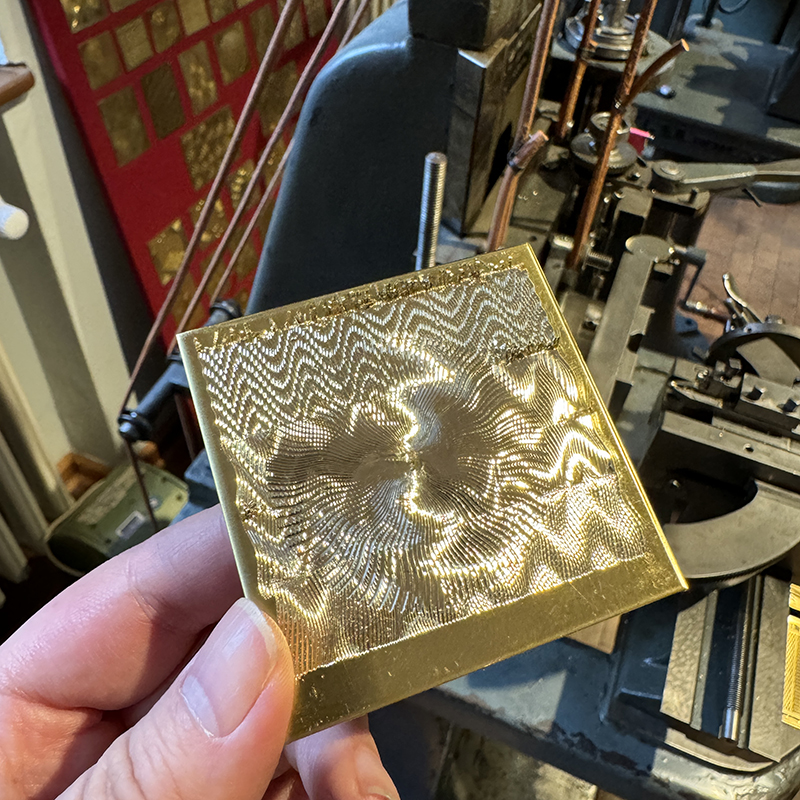

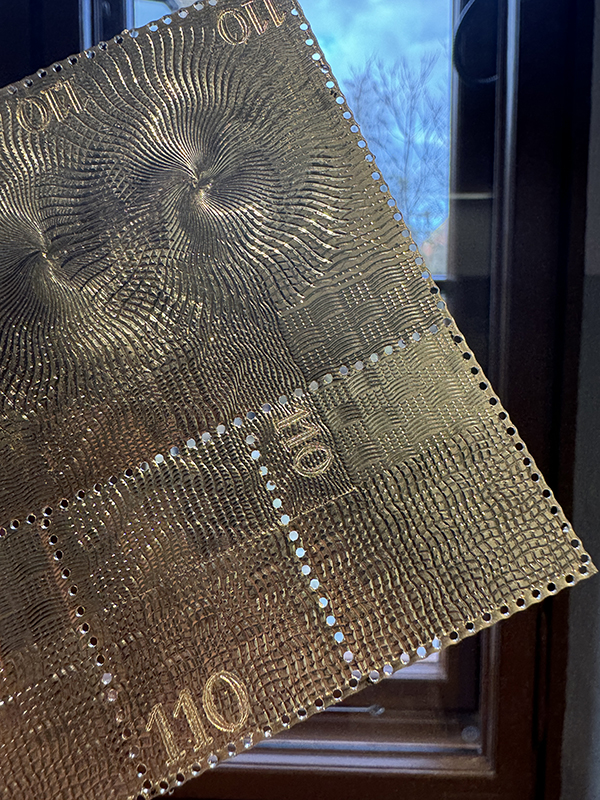

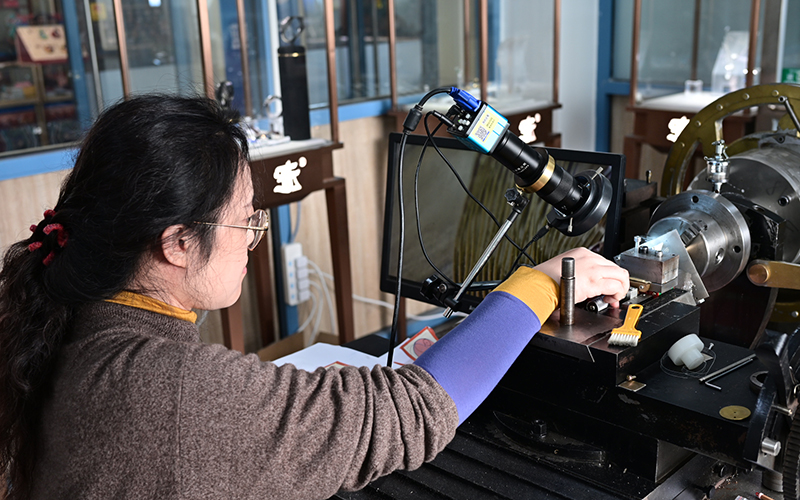

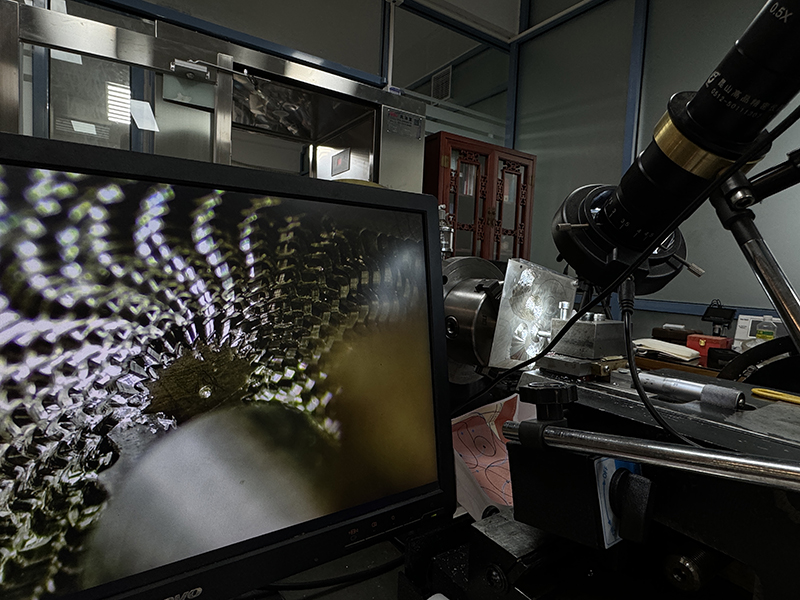

In one strand of experimentation, I guilloched pattern with different depths and directions on the plate and discovered that the sequence can affect the final visual outcome. By varying the radius of the motifs, I made a swirl with Guilloché machine -- an optical dynamic pattern where a flat plate shifts its appearance depending on the viewer's angle.

This transformation of engraved lines reminded me of the visual language found in coins and postage stamps. Like those official mediums, stamping transfers the contours of the die onto metal, serving not only as a formal impression but also as a symbolic act of authorization—akin to the minting of currency or the issuing of state seals.

Simultaneously, the engraved patterns and the accumulation of metal shavings evoked associations with woven textiles. This inspired me to create a patchwork stamp brooch, combining Guilloché and stamping. I wove strips of guilloché-engraved brass and silver, and constructed a brooch with a backing structure that further reinforced its textile-like appearance.

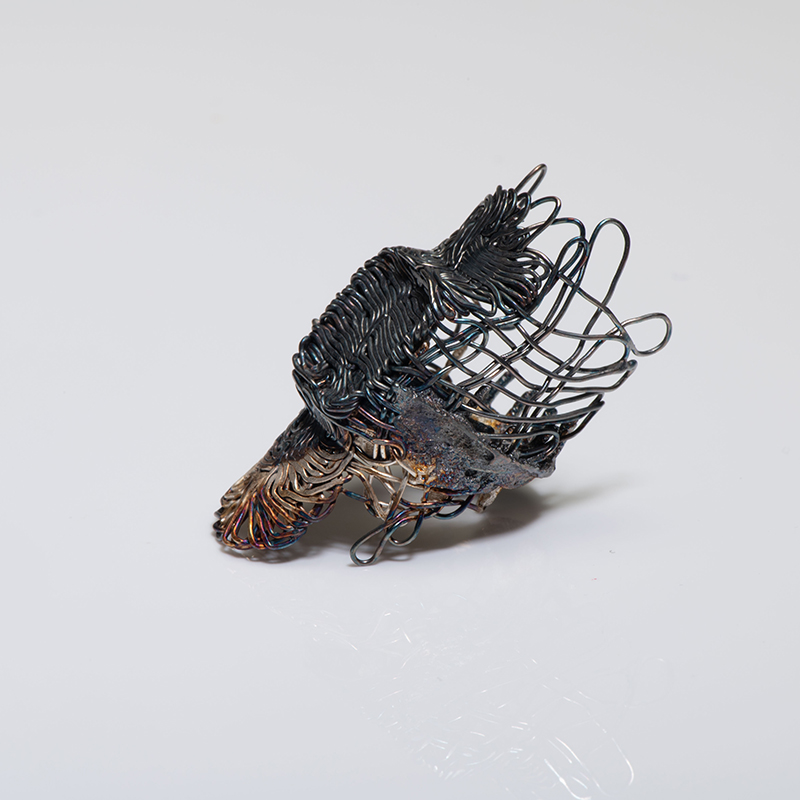

In another variation, I sewed coiled wires onto a guilloché plate and then stamped them together. This process brought a three-dimensional quality to the previously two-dimensional guilloché lines. The gaps between the silver wires produced an illusion of hollowness, creating a compelling visual rhythm that plays with light, depth, and structure.

3. Prism of time and space

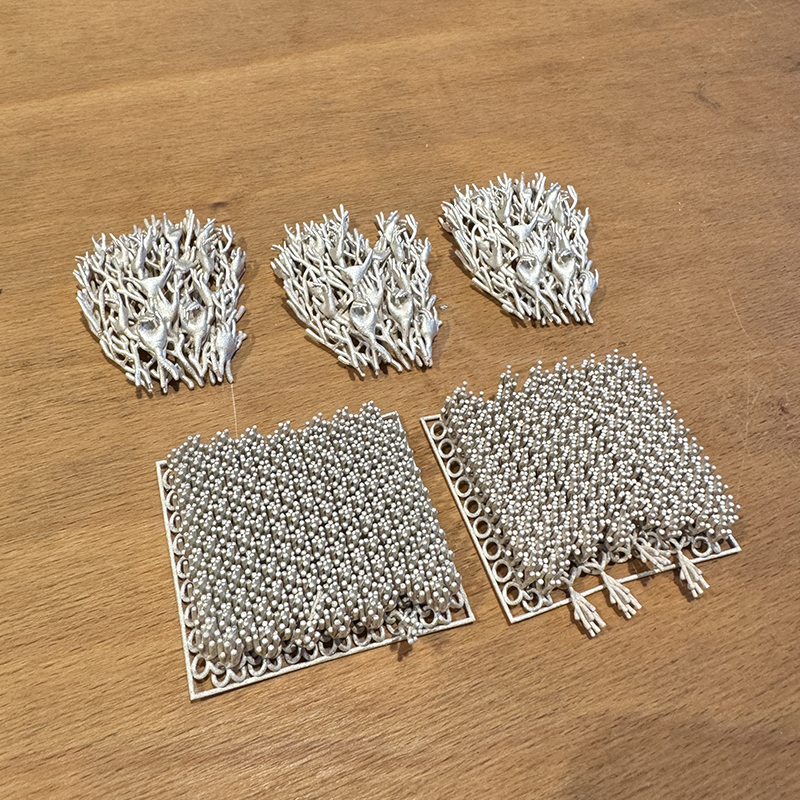

Thanks for support and sponsor from C. Hafner, I was able to do a series of attempts, exploring the possibility to combine 3D-Print technology with historic technology available in the museum. For this series, titled Prism of Time and Space, I designed two mycelium-inspired structures with flat bases for ease of stamping. One was a conventional, radiating form, while the other featured a more complex, two-layered system. My original intention was to stamp animal motifs onto these branching structures, observing how force would interact with their porous, lattice-like construction. I imagined that unstamped areas would retain a matte finish and three-dimensionality, contrasting with the compressed, detailed surfaces.

Creating these divergent branches is a dynamic process for me. are symbolized by human figures — such as Medusa or the Thousand-Armed Avalokitesvara — where multiplicity is tied to perception and power. The hand, as a tool for control and connection, became a natural extension of this idea. I experimented by attaching sculpted hands to the tips of the branches. Afterwards, threads would be pulled in these hands. I am interested in how force from different material will transform the structure. This demanded extensive testing and refinements, particularly in reinforcing the fragile connections and adjusting gestures. In the test piece, the connection between the hand and the branch is relatively thin and fragile, so in the next version, I bolded these parts

Although the final printed model captured fine details such as finger articulation, it revealed surface cracks that required repair. I used hard solder and annealing to stabilize the silver structures before stamping.

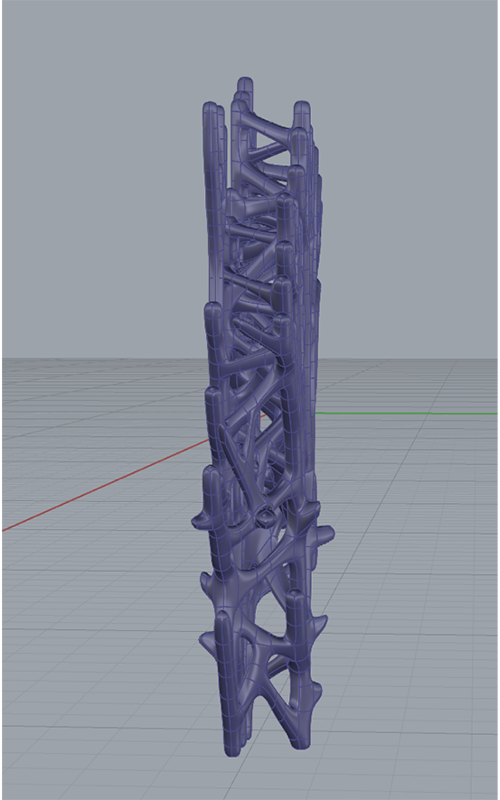

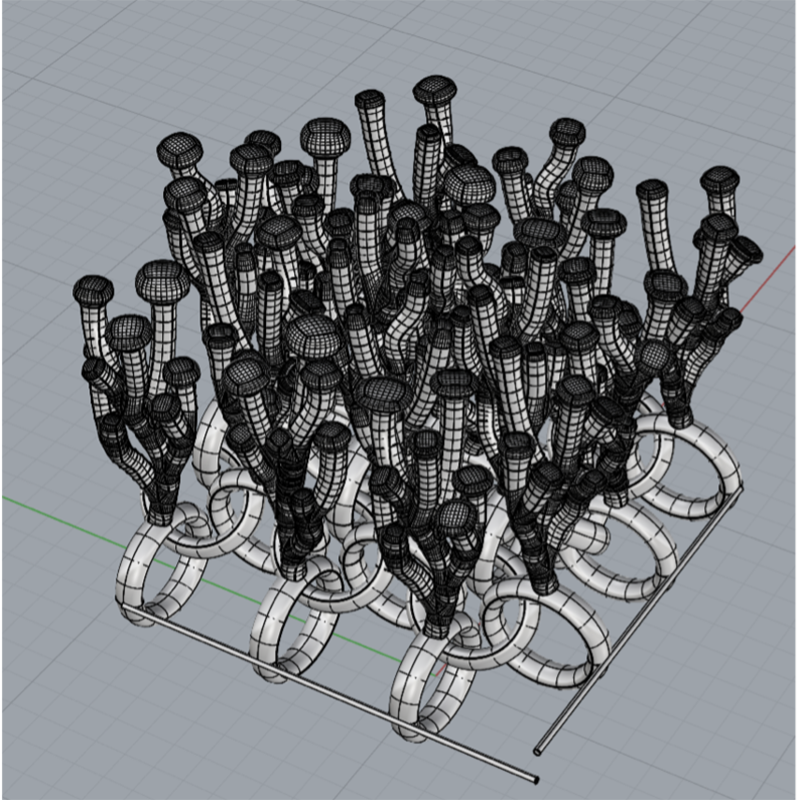

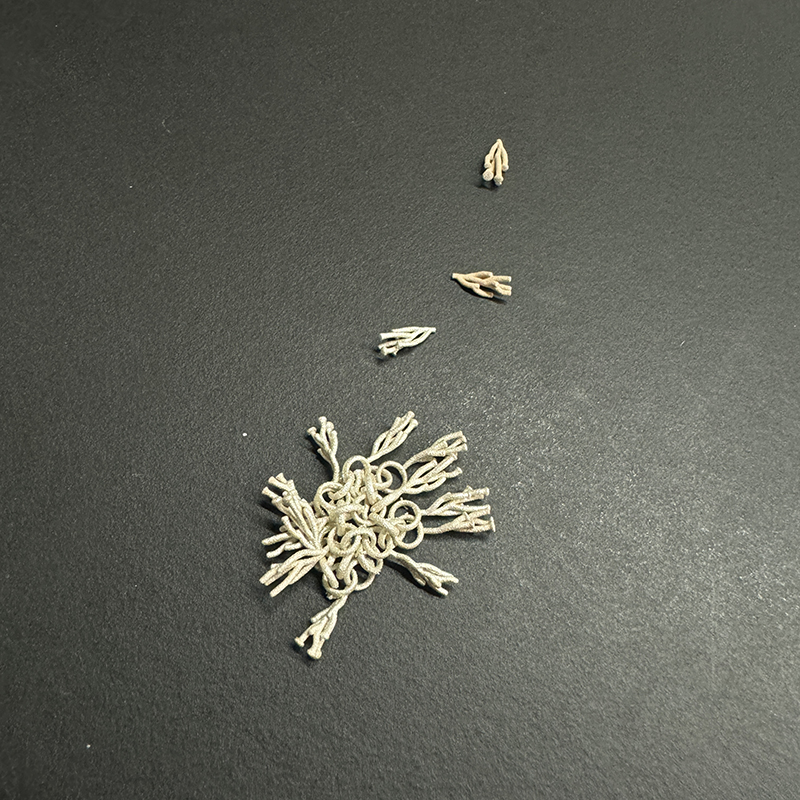

My interest in the impact of stamping deepened during this process. Stamping is a process commonly used in mass production. With a single thunderous strike, it gives voice to the material —merging all differences into a new, unified whole in an irresistible way. In a previous project, I set standing nails into a die to visualize force as it radiated outward—like wheat bending in the wind. This inspired me to design more intricate 3D-printed forms where the impact of stamping on duplicated flexible structures could be observed more clearly. One such flexible model involved interlinked branches connected by small rings The greatest challenge here was to take two aspects into account. The first is available angles in printing, in order to avoid or reduce support aids that are difficult to remove. The second is to make the movable structure after being printed remain standing neatly, so that it can be stamped from a relative controlled direction. After an initial failure, I improved the connections and added auxiliary support wires, which could be removed post-process. The second iteration of the printed model proved structurally successful.

l

l

t

Yet, new challenges arose during stamping. 3D-printed silver possesses a different quality from milling or casting silver, making it under the force of stamping form a mosaic-like texture. It prompted me to find structural supports for the silver components.

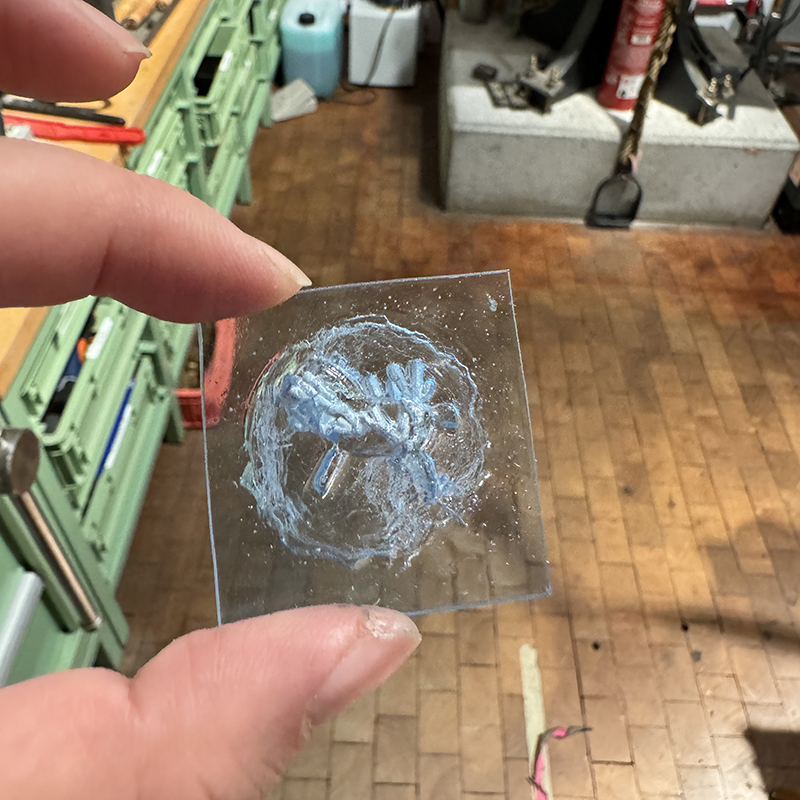

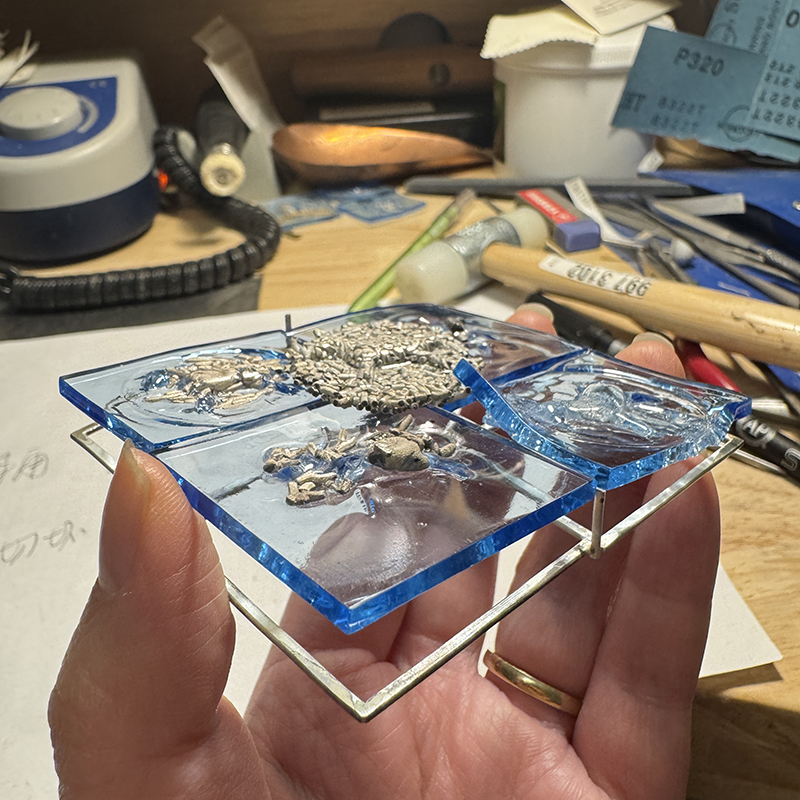

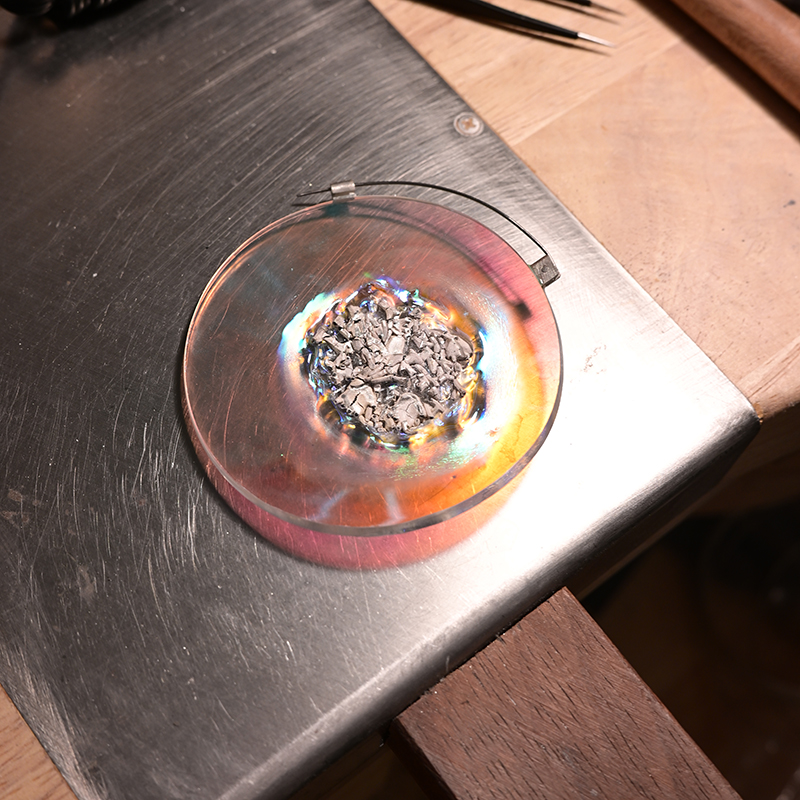

Initially, I used melted nylon threads as filler for fractured zones. Later, I came up with an idea to use acrylic glass as a support part. When heated, acrylic becomes malleable and can conform under

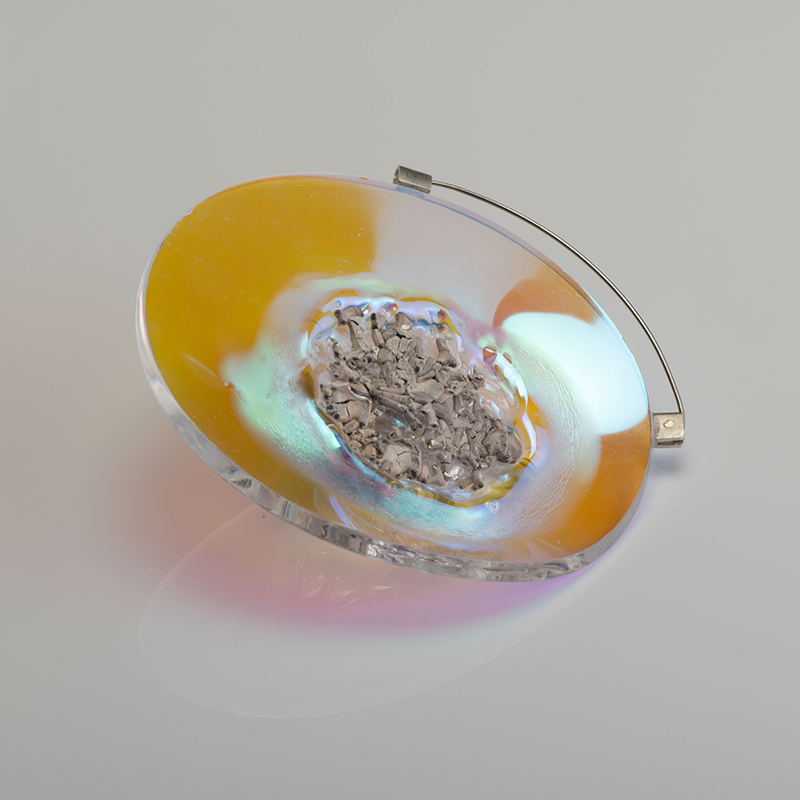

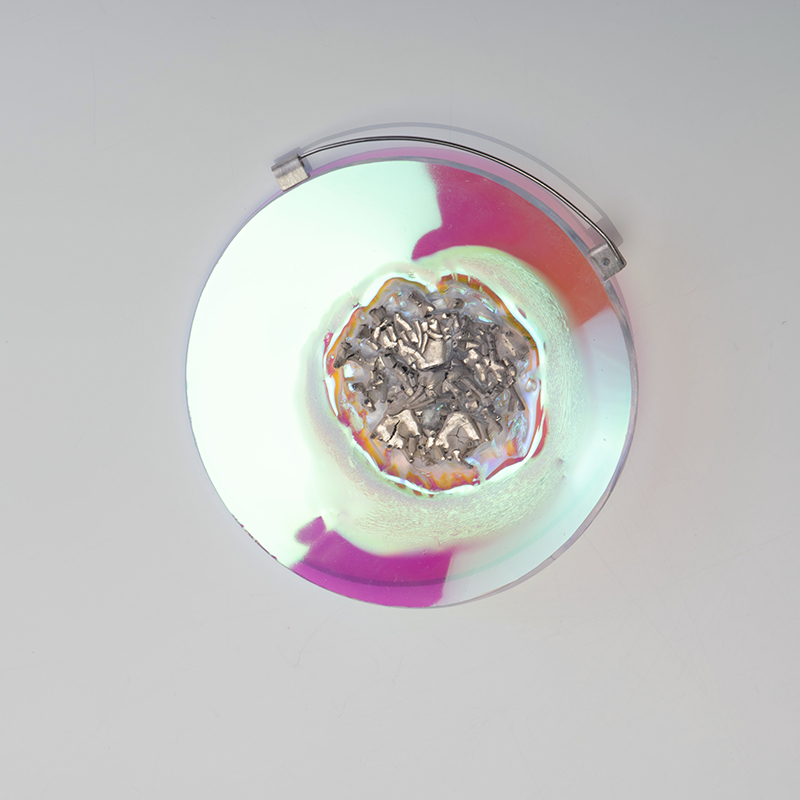

pressure; when cooled, it hardens. I stamped the silver together with softened acrylic, and the results were unexpectedly successful. The juxtaposition of mosaic-like silver fragments with the solidified acrylic created objects that resemble modern archaeological artifacts—contemporary relics made with modern and historical techniques preserved in synthetic amber.

Acrylic, a relatively less rigid material, becomes the bearer of metal. It breaks the original form of the design and challenges our preconceptions of materials. The silver, like an ink pad, reveals another side of its material qualities through the act of stamping. The distinctions between the precious metals and affordable materials became blurred, dissolving traditional material hierarchies.

In another variation, the stamped acrylic, through heat treatment, provides structural support to the printed silver elements and binds them into a tightly fused whole. The force deformed the laser-coated acrylic, bending it slightly and enriching its color palette through subtle changes in reflection—creating a spectrum that shifts with the viewer’s position.

Realizing that the clarity of the stamped contour relies heavily on the precision of the negative die, I made a brass die which can be set on the steel negative die. I later digitized select molds to preserve and reproduce them using modern techniques. While geometric patterns translated well to this method, highly detailed organic motifs—such as animals—proved difficult to replicate without hand finishing, reminding me that some processes resist full automation.

Activities during the scholarship residence in the museum

Throughout the residency, I had the opportunity to participate in a wide range of enriching workshops, not only within the jewellery department but also in other department in the museum. These interdisciplinary encounters allowed me to expand my technical repertoire and deepen my understanding of material expression. I engaged in practical sessions where I learned new techniques and methodologies, broadening the scope of my creative vocabulary.I took part in the Zeughausmesse, exhibited and explained my work in process and other scholarship holders’ work. This public presentation allowed for dialogue with a broader audience and facilitated valuable exchanges with fellow artists and visitors. Sharing the conceptual evolution of my project alongside others' diverse approaches was a meaningful experience. It underscored the dynamic and collaborative spirit of the residency and contributed to the vivid tapestry of memories that I associate with my time in the museum.

Continued development of the project

After returning to China, I remained deeply engaged with the ideas developed during the residency. One significant opportunity arose when I was invited to design a table tennis racket featuring a Guilloché pattern for Wallpaper magazine. This project posed a new challenge, as I did not have direct access to a Guilloché machine. I began researching the technique further and initiated contact with local companies.

Through this inquiry, I discovered two prevalent methods for producing Guilloché patterns in China: one employing custom-built manual machines, and the other integrating CNC technology. I eventually collaborated with a specialist company that produces watch faces and also works with enamel. Their self-built Guilloché machine—optimized for creating circular patterns—was the tool I used to develop the design. This limitation inspired a refined approach to pattern planning and engraving, which ultimately enriched the outcome.

Photos:

Petra Jaschke (final works)

Lingjie Wang (process)